“In order to gain and to hold the esteem of men, wealth must be put in evidence.” This was the contention of Thorstein Veblen, who in 1899 first identified the concepts of status-seeking through conspicuous consumption (even though evidence of it stretches as far back as ancient Egypt). The American economist also recognised a group of commodities whose demand is proportional to their price by contradicting the basic economic laws of supply and demand. These would later become known as ‘Veblen goods’.

Veblen goods combine the intrinsic value of luxury goods with deliberately increased price tags that convey a symbol of success through status. For example, the car you drive. Nothing says success quite like a Rolls Royce.

When you buy a luxury car, you don’t necessarily buy one because it is the fastest, the safest or the most efficient car on the market. You buy one because of the prestige of the brand and because of the design and build quality.

When it comes to the luxury car market, it is true that Rolls Royce command the highest prices because they have no equal. They go the extra mile to ensure that their vehicles are the best money can buy such as featuring lavish hand finished wooden interiors individually fitted by skilled artisans.

These careful, expensive and time-consuming dedications toward perfection are eventually reflected in the price tag, but you’re still paying for something more than mere production and labour costs. You’re paying for a hidden multiplier that creates status through ultra-exclusivity boosting its perceived desirability and value to such an extent that sales go up, rather than down.

Veblen goods are the economy of status. If you’re driving a Porsche, you might be doing all right for yourself, but if you’re driving a Phantom you are, quite simply, the man. Owning one shows that you belong to a particular social circle. Accordingly, the goods, whether it be a unique piece of jewellery, a case of fine wine or a rare work of art, are desired as much for the cost as for their quality.

Evidence that astronomical prices are about exclusivity rather than a reflection of production costs can be found in some designer clothes. A Saint Laurent jacket with a £40,420 price tag was revealed to be made of 80% polyester, a cheap synthetic. Analysts, not designers, will often determine pricing decisions based on what they predict the item will sell for as opposed to what they cost to make.

Where does value fit into all this? If you’re one of the squeezed middle class or lower down on the financial ladder you will most likely argue quite simply that it doesn’t. The notion of making a product deliberately over-priced certainly doesn’t sound like good business practice on the surface of it, but the evidence suggests otherwise.

In 18 years the price of a Hermès Kelly bag has jumped from $4,800 to $15,600 and in 15 years, the Manolo Blahniks made famous by Sex and the City character Carrie Bradshaw, have risen in price from $485 to $925. Upward pricing policies that are apparently oblivious to that pesky global financial crisis and its circuitous fallout.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the cost of luxury goods, many of which are considered Veblen goods, has risen by 60 per cent in a decade. Some in the industry blame this on the rising cost of raw materials, but insiders believe they are raised purely to increase appeal.

Returning to the question of value, to the price insensitive affluent, Veblen goods are essential means of conveying a positive message about themselves to the public, making them practically priceless.

This only perpetuates the negative pricing elasticity of Veblen goods – to prove your status through wealth you have to keep buying higher to distinguish yourself as above everyone else. Just ask James Stunt, he purchased the last known portrait of Anthony Van Dyck for the tidy sum of £12.5 million, presumably because he is simply running out of things to buy.

In the world of the high net worth individual, status is king. To highlight the absurdity of value placed upon social status among the wealthy, refer to a passage from Bret Easton Ellis’s transgressive satire, American Psycho, where a group of slick Wall Street traders sit around comparing business cards at a high-powered meeting. “Look at that subtle off-way colouring, the tasteful thickness of it” the novel’s main protagonist, Patrick Bateman whispers to himself “Oh my god, it even has a watermark!” he continues in the middle of a creeping anxiety attack.

Never mind the fact that here is a guy who spends his spare time casually torturing escorts without a sliver of any identifiable human emotion, present a prettier piece of miniature cardboard to market yourself than he possesses and watch his world fall apart.

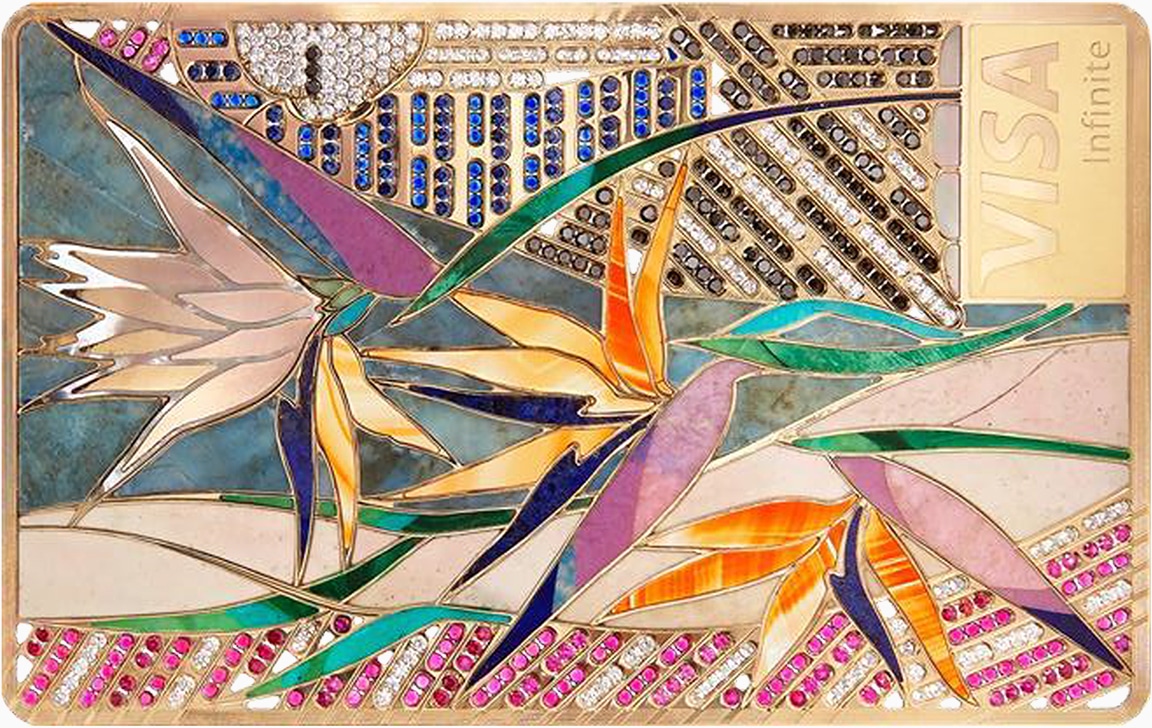

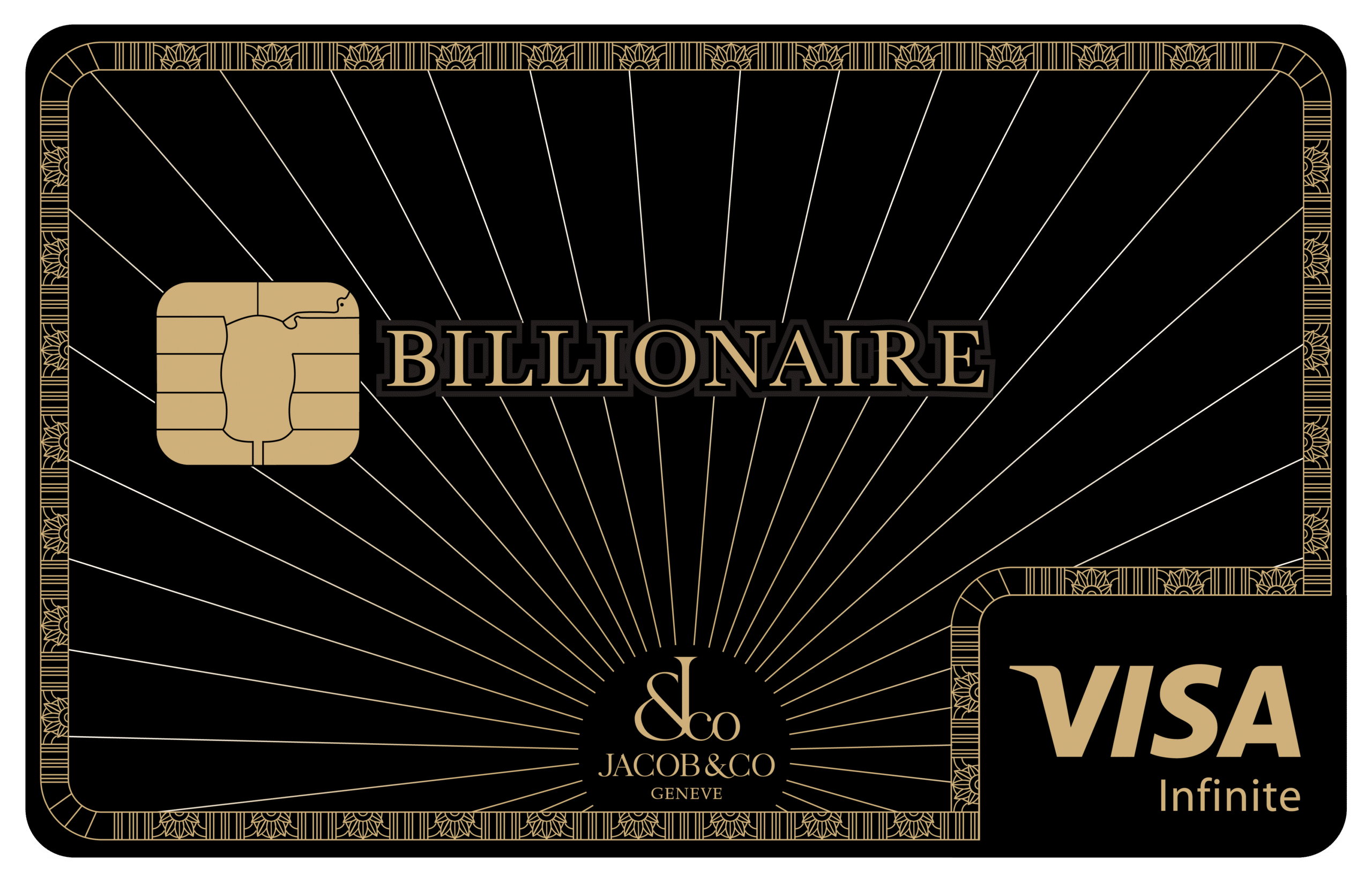

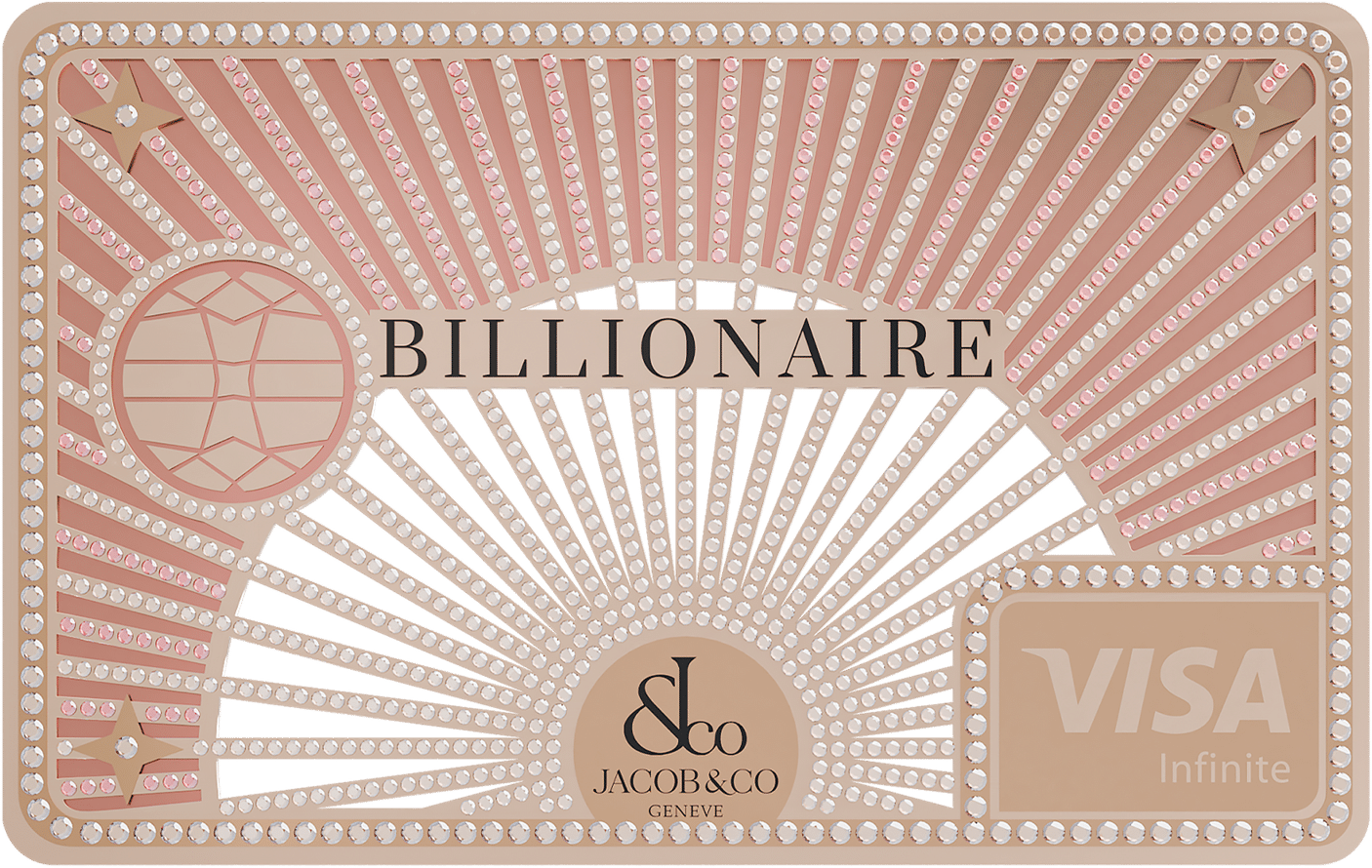

An extreme example perhaps, but not too detached from the realities of keeping up appearances in the upper echelons of elite society. Status is the sole reason Bergdorf blondes can’t be seen in public without their Hermès Birkin or members of the billionaires’ boys club revel in taking every conceivable opportunity to pull whichever exclusive credit card is currently trending from their Gucci crocodile skin wallets.

Status does have a nasty habit of changing on us though. Studies have shown that consumers are willing to sacrifice luxury and performance to a benefit perceived social status, for example, an environmentally friendly hybrid opposed to gas-guzzling sports car. The former might not have the oomph of the latter, but it goes some way to signalling that the owner is an environmentally conscious person opposed to a selfish individual concerned primarily more about his own comfort than the welfare of the community and surely just being a nice guy does more for your status than a Hermès Birkin, doesn’t it?